The news yesterday that the teaching of foreign languages in English secondary schools is in steep decline, disappearing from the curriculum in large parts of the country, was sad, but hardly surprising.

One striking example is that thirty-seven local authority areas, including some of the poorest (North Tyneside, Knowsley, Wigan, Rochdale) now enter fewer pupils for foreign language exams than the elite Eton College.

I did French and German to "A" Level in the late 80's, but never felt really confident about speaking them in a real life situation until the last decade or so, when I started going to Germany and the French-speaking part of Belgium on beer trips, and was pleasantly surprised how much came back within a few hours of my being there.

Apparently foreign languages, especially French and German, are seen as too hard, both by students choosing which subjects to study to GCSE and their teachers. A big part of that is exam results counting towards a school's position in the league tables, and hence their funding. And of course, once people stop studying foreign languages at school it has a knock-on effect on both the number of undergraduates studying them at university and those qualified to teach them.

I was also one of the last half dozen people to take "O" Level Latin at a state school in Stockport, although sadly I don't get much chance to use it now.

Showing posts with label language. Show all posts

Showing posts with label language. Show all posts

Thursday, 28 February 2019

Monday, 4 January 2016

The Sense of Style

I always read a book at Christmas, usually non-fiction, and for the one just gone I picked The Sense of Style by Steven Pinker

I first heard Pinker's name when I did a part-time course in teaching English as a foreign language at Manchester College of Arts and Technology twenty years ago. Along with Noam Chomsky and Stephen Krashen, he's a leading academic in the field of language acquisition theory.

The Sense of Style is a guide to English grammar and usage which, among other things, looks at commonly confused words ("disinterested"/"uninterested", "enormousness"/

"enormity"), the minefield of "lie, lay, laid, lain", the singular "they" for men and women, and whether to punctuate quotation marks the American way "like this," or the British way "like this". Pinker prefers the latter, dismissing the former as aesthetic fussiness by printers, and is pretty liberal when it comes to things most grammar experts frown upon (splitting infinitives and misusing "less"/"fewer"). It's a handy book for anyone who regularly attempts to turn out decent English prose, whether on a blog or elsewhere.

I first heard Pinker's name when I did a part-time course in teaching English as a foreign language at Manchester College of Arts and Technology twenty years ago. Along with Noam Chomsky and Stephen Krashen, he's a leading academic in the field of language acquisition theory.

The Sense of Style is a guide to English grammar and usage which, among other things, looks at commonly confused words ("disinterested"/"uninterested", "enormousness"/

"enormity"), the minefield of "lie, lay, laid, lain", the singular "they" for men and women, and whether to punctuate quotation marks the American way "like this," or the British way "like this". Pinker prefers the latter, dismissing the former as aesthetic fussiness by printers, and is pretty liberal when it comes to things most grammar experts frown upon (splitting infinitives and misusing "less"/"fewer"). It's a handy book for anyone who regularly attempts to turn out decent English prose, whether on a blog or elsewhere.

Wednesday, 26 September 2012

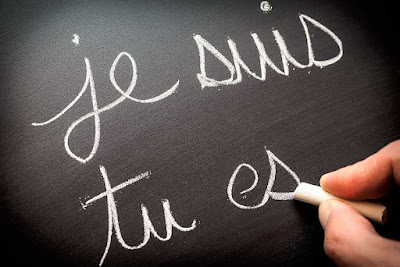

Bonjour, Guten Tag, Buenos días

Today is European Day of Languages, an annual event organised by the Council of Europe to promote "the importance of language learning" and celebrate "the rich linguistic and cultural diversity of Europe".

I can speak fairly decent French and German. Although I studied them both to A Level, up until a couple of years ago I'd have said that I hadn't remembered much of either from my school days twenty-five years ago. When I first went to Germany though I was pleasantly surprised how much came back to me and how much my spoken German improved after a few days there. I hope the same's true of my French, a theory I'm intending to test by going to Brussels and Walloon Brabant next summer.

What does this say then about language teaching in schools? Having studied theories of language acquisition on a Teaching English as a Foreign Language course in the mid-90's, I think it confirms the idea put forward by Stephen Krashen that the key to learning a language is "comprehensible input" (i.e. lots of exposure to spoken language) and specifically "i+1", that is language that is just beyond the level the learner has reached.

I know from my younger relatives that they spend far more time speaking and listening in language lessons at school than I ever did and while learning vocabulary and grammar does give you a grounding in a language, copying stuff off the blackboard isn't the most effective way of doing it.

I can speak fairly decent French and German. Although I studied them both to A Level, up until a couple of years ago I'd have said that I hadn't remembered much of either from my school days twenty-five years ago. When I first went to Germany though I was pleasantly surprised how much came back to me and how much my spoken German improved after a few days there. I hope the same's true of my French, a theory I'm intending to test by going to Brussels and Walloon Brabant next summer.

What does this say then about language teaching in schools? Having studied theories of language acquisition on a Teaching English as a Foreign Language course in the mid-90's, I think it confirms the idea put forward by Stephen Krashen that the key to learning a language is "comprehensible input" (i.e. lots of exposure to spoken language) and specifically "i+1", that is language that is just beyond the level the learner has reached.

I know from my younger relatives that they spend far more time speaking and listening in language lessons at school than I ever did and while learning vocabulary and grammar does give you a grounding in a language, copying stuff off the blackboard isn't the most effective way of doing it.

Tuesday, 17 July 2012

A few of my least favourite things

I was listening to a policeman on Radio 4's Today programme before, talking about G4S and their completely predictable failure to provide sufficient security staff for the Olympic Games.

I was listening to a policeman on Radio 4's Today programme before, talking about G4S and their completely predictable failure to provide sufficient security staff for the Olympic Games.Every other sentence was "going forward", "working with our partners", "rolling out". As George Orwell wrote in Politics and the English Language, "political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible...Thus political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness." Meaningless corporate speak is everywhere. I don't think it's consciously learnt or adopted, just picked up by people to fit into an organisation. I had a manager when I worked in the civil service who spoke almost entirely in this language, she was forever "touching base", "cascading information" and "flagging up". In meetings, we'd sit on the front row, notepads on our knees, listening intently. She thought we were hanging on her every word, which we were but only because of the buzzword bingo game we were playing.

The way to deal with this kind of language is to act dumb and pretend you don't understand. When the manager in the civil service once told us that she'd "touch base again next week", one of my colleagues asked her if that meant she'd be coming to see us again and, somewhat thrown, she replied, "Er, yes".

Not quite as bad as corporate speak but equally infectious it seems is what's variously called up-speak, high-rising terminal or Australian Question Intonation, that is the compulsion to go up at the end of every sentence. It doesn't obscure meaning like corporate speak does but it's quite distracting once you start noticing it. I don't know what can be done to combat it although some people suggest that you should treat every statement made in AQI as a question and answer it.

The solution to my very least favourite thing - people on the platform crowding up against the doors when you're trying to get off a train - is simple: guards armed with electric cattle prods.

Wednesday, 6 June 2012

The Queen's English

A society set up to promote the correct usage of English grammar has decided to disband.

The Queens English Society say that popular indiferrence to the inapropriate use of apostrophe's and spelling words korrectly mean that it cant continue. I dont kno what they mean, do u?

The Queens English Society say that popular indiferrence to the inapropriate use of apostrophe's and spelling words korrectly mean that it cant continue. I dont kno what they mean, do u?

Wednesday, 30 May 2012

How's that spelt?

According to a study of children's writing by the Oxford University Press, young people are increasingly using American words.

I'm not that bothered about American words being used - it's pretty much inevitable given the influence of film, TV and music. What puzzles me is the seemingly recent spread of American spellings such as "city center" and "TV program". Where has it come from and why now? You can't even blame it on Australian soap operas as you can with uptalking.

I'm not that bothered about American words being used - it's pretty much inevitable given the influence of film, TV and music. What puzzles me is the seemingly recent spread of American spellings such as "city center" and "TV program". Where has it come from and why now? You can't even blame it on Australian soap operas as you can with uptalking.

Wednesday, 9 May 2012

A talent for language

Last night on Channel 4, Hidden Talent looked at how people learn languages. It's something I've been interested in since studying theories of language acquisition as part of a teaching course at Manchester College of Arts and Technology in the mid-90's.

I broadly agree with those - including Chomsky, Krashen and Pinker - that humans have an innate abilty to learn languages ("Language Acquisition Device") and that the key to doing so is exposure to a level of language just beyond what you understand ("comprehensible input", or i+1, in linguistic jargon).

The programme touched on some of the issues around language acquistion. Learning a foreign language is not the same as learning your first one but there are some shared features such as being motivated to learn (a "low input filter"), not afraid to make mistakes (a "low output filter") and prepared for the the "unexpected answer", for example: "Which way is it to the town centre?", "I'm sorry, I'm not from here."

A lot of what they argue rings true to me. I studied German to A Level but only went to Germany for the first time three years ago. I was pleasantly surprised how quickly things I thought I'd forgotten came back, my increased fluency after a few days/beers and the increased friendliness of people when you speak their language, despite or even because of a few grammatical errors.

The Channel 4 programme was moving at another level. The person chosen as a guinea pig was a young homeless guy living in a hostel who had dropped out of college and become estranged from his family. In the process of learning Arabic (referred to strangely by the programme makers as "one of the world's most complex languages"), he travelled to Jordan, where after a few weeks he was fluent enough to do a live TV interview, and also was reconciled with family. You could argue - and I would - that most people exposed to a language for a lengthy period will learn it but even so his was still an impressive achievement.

I broadly agree with those - including Chomsky, Krashen and Pinker - that humans have an innate abilty to learn languages ("Language Acquisition Device") and that the key to doing so is exposure to a level of language just beyond what you understand ("comprehensible input", or i+1, in linguistic jargon).

The programme touched on some of the issues around language acquistion. Learning a foreign language is not the same as learning your first one but there are some shared features such as being motivated to learn (a "low input filter"), not afraid to make mistakes (a "low output filter") and prepared for the the "unexpected answer", for example: "Which way is it to the town centre?", "I'm sorry, I'm not from here."

A lot of what they argue rings true to me. I studied German to A Level but only went to Germany for the first time three years ago. I was pleasantly surprised how quickly things I thought I'd forgotten came back, my increased fluency after a few days/beers and the increased friendliness of people when you speak their language, despite or even because of a few grammatical errors.

The Channel 4 programme was moving at another level. The person chosen as a guinea pig was a young homeless guy living in a hostel who had dropped out of college and become estranged from his family. In the process of learning Arabic (referred to strangely by the programme makers as "one of the world's most complex languages"), he travelled to Jordan, where after a few weeks he was fluent enough to do a live TV interview, and also was reconciled with family. You could argue - and I would - that most people exposed to a language for a lengthy period will learn it but even so his was still an impressive achievement.

Wednesday, 4 April 2012

AI and language

BBC2 has dumbed down a lot in the last decade or so, shifting arts and music programmes to BBC4 and replacing them with cookery and interior design shows. But it still manages to broadcast some thought-provoking stuff too and last night's episode of the science series Horizon was certainly that.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has still to reach the level where robots can think like humans do but we are further down that road than many people - including myself - had realised. By far the best bit was at the end when presenter Marcus Du Sautoy went to a lab where two robots are teaching each other a new language they have invented, making up words for movements, shapes and colours. To paraphrase the 60's Chicago DJ Pervis Spann talking about people who don't like blues, if you weren't touched by the scene you've got a hole in your soul. Above all, it reminded me of one of my favourite films from childhood, Silent Running, in which hippy ecologist Bruce Dern teaches robots Huey and Dewey to garden on board a space ship containing the environmentally devastated Earth's last forest before killing his crewmates and then himself, blasting the forest on a journey into deep space.

One of the pioneers of AI, Seymour Papert, was incidentally a member of the Socialist Review Group when he lived in Britain in the 50's.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has still to reach the level where robots can think like humans do but we are further down that road than many people - including myself - had realised. By far the best bit was at the end when presenter Marcus Du Sautoy went to a lab where two robots are teaching each other a new language they have invented, making up words for movements, shapes and colours. To paraphrase the 60's Chicago DJ Pervis Spann talking about people who don't like blues, if you weren't touched by the scene you've got a hole in your soul. Above all, it reminded me of one of my favourite films from childhood, Silent Running, in which hippy ecologist Bruce Dern teaches robots Huey and Dewey to garden on board a space ship containing the environmentally devastated Earth's last forest before killing his crewmates and then himself, blasting the forest on a journey into deep space.

One of the pioneers of AI, Seymour Papert, was incidentally a member of the Socialist Review Group when he lived in Britain in the 50's.

Tuesday, 20 March 2012

Language in our nature?

In the mid-90's, I did a part-time course in teaching English as a foreign language at Manchester College of Arts and Technology. One of things we studied was theories of language acquisition and it's something I've been fascinated by ever since. The mainstream theory of language aqcquisition since the 1970's - developed by Noam Chomsky, Stephen Krashen, Stephen Pinker and others - is centred on the idea of a Language Acquisition Device (LAD), a innate genetically transmitted ability unique to humans which allows children to instinctively learn their native language. This means that grammatical features (tenses, plurals etc.) appear in children at the same time whatever that language is.

I was interested therefore to read about a new book by one Daniel Everett which apparently seeks to overturn the LAD theory of language acquisition on the strength of a language called Pirahã spoken by around three hundred people in the Amzonian region of Brazil and which Everett claims doesn't include these grammatical features.

There are a number of holes that can be put in Everett's claims: he is the only non-native speaker of Pirahã and there is no way of knowing if what he says about the language is true (even if he thinks it is, there is no saying that the he has picked up all its nuances from the native speakers). He also seems to have oversimplified what Chomsky says about language acquisition in order to try to knock his theories down. But the killer point to me - and one the Guardian review doesn't really deal with, possibly for reasons of undue politeness or liberal sensibilities - is that Everett is an evangelical Christian and former missionary who travelled to Amazonia to convert the native peoples and whose only reason for learning Pirahã was to translate the Bible into it. Whatever Chomsky's political faults, I'd trust his rational judgements on language acquisition over Everett's any day of the week.

I was interested therefore to read about a new book by one Daniel Everett which apparently seeks to overturn the LAD theory of language acquisition on the strength of a language called Pirahã spoken by around three hundred people in the Amzonian region of Brazil and which Everett claims doesn't include these grammatical features.

There are a number of holes that can be put in Everett's claims: he is the only non-native speaker of Pirahã and there is no way of knowing if what he says about the language is true (even if he thinks it is, there is no saying that the he has picked up all its nuances from the native speakers). He also seems to have oversimplified what Chomsky says about language acquisition in order to try to knock his theories down. But the killer point to me - and one the Guardian review doesn't really deal with, possibly for reasons of undue politeness or liberal sensibilities - is that Everett is an evangelical Christian and former missionary who travelled to Amazonia to convert the native peoples and whose only reason for learning Pirahã was to translate the Bible into it. Whatever Chomsky's political faults, I'd trust his rational judgements on language acquisition over Everett's any day of the week.

Monday, 26 September 2011

Language is our nature

Stephen Fry's new series on language started on BBC2 last night. Having studied language acquisition years ago when I was doing a part-time teaching course at Manchester College of Arts and Technology, I was familiar with those whose theories he outlined, Chomsky, Pinker (and Krashen who surprisingly wasn't mentioned by name) but there was also a lot of interesting stuff about DNA and language.

Fry's pretty watchable whatever he's talking about and if you missed it I recommend watching it here.

Fry's pretty watchable whatever he's talking about and if you missed it I recommend watching it here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)